Travel has a wonderful way of immersing us in the moment. As you connect with a place, swept up in the grandeur and awe, normal confines fall away, leaving you instead with the blissful here and now - an acute awareness of where you are in the world, and just how lucky you are to be there. Perhaps you’ll be overwhelmed by a beach scene so pristine it will rob you of words, or find yourself alone on a hillside, the alpine air whipping up around you, a verdant expanse at your feet. You’ll notice the scent of pine, the traces of salt, the chatter of birds. In the presence of such beauty, you might also experience a flash of clarity, a sudden awareness of what is truly important … or exactly where you want to be.

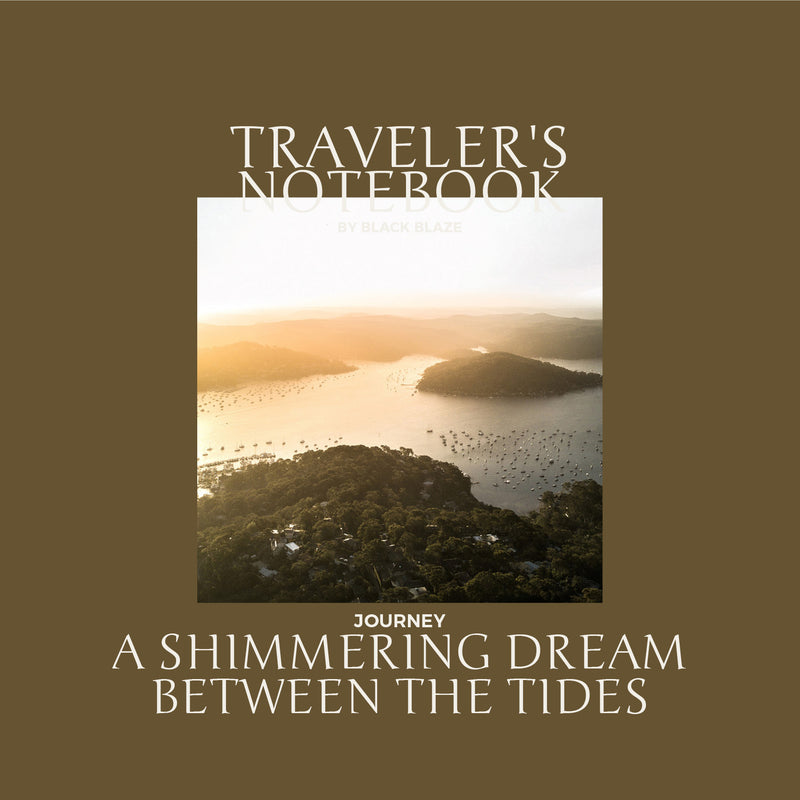

For a long time, I believed that you had to be there - seeing, savouring, doing - to encounter such moments. But a few years ago, with our borders suddenly closed, I found that I could experience the bliss I’d long associated with travel by getting lost in the photographs of others.

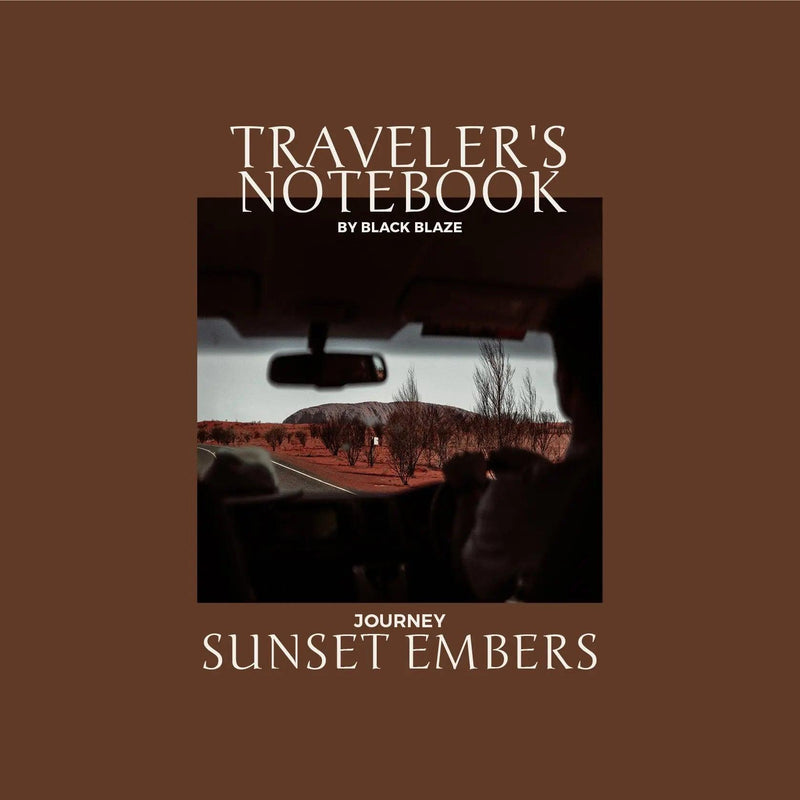

It’s surprisingly easy to fall in love with a place from afar - to swoon over the colour and warmth captured in a particularly striking image. And this is exactly what I did while pouring over a friend’s photos from a trip through the South Australian outback nearly a decade ago. Looking at them - the dazzling blues, the fire-bright reds, the dustings of sage, rust and gold - the landscapes didn’t seem entirely real, but I could imagine myself there nonetheless.

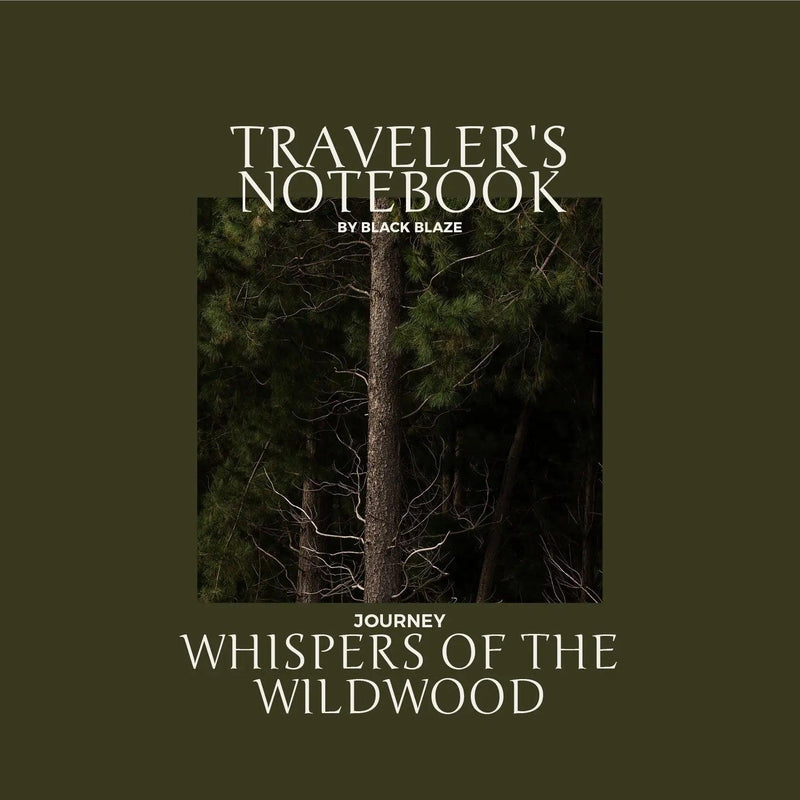

She’d taken the photographs in Ikara-Flinders Ranges National Park, a 95,000-hectare-wide desert oasis found 430-kilometre north of Adelaide (it’s a little further if you chose to roam through the Clare Valley’s wineries en route). It is home to Ikara (Wilpena Pound), a natural amphitheatre that rises like a juggernaut from the heart of the surrounding national park. Although it is the undeniable centrepiece, beauty is everywhere. In the trees guarded by flocks of galahs, in the carpets of curiously-shaped Sturt’s desert peas, in the walking trails draped across the orange earth, and in the yellow-footed rock-wallabies basking in the afternoon sun.

Ikara-Flinders Ranges National Park, with its rugged peaks and verdant gorges, boasts 800-million years of geological history. The Heysen Trail (a long-distance walking route that stretches from Parachilna to Cape Jervis in the Fleurieu Peninsula) passes by, and the 20-kilometre ‘Corridors through Time’ Geological Trail in Brachina Gorge reveals one of the country’s best records of sedimentary rock deposits. Fittingly, this was the first location in the Southern Hemisphere to be declared a site of international geological significance, with the ancient rocks containing both Precambrian unicellular fossils and the multicellular lifeforms of the Cambrian Period.

Chatting to the photographer, she spoke about the beauty of Sacred Canyon’s rock engravings (carved out thousands of years ago by the Adnyamathanha people), the views from Tanderra Saddle (which requires a little scrambling the climb), and the power of Malloga Falls in Edeowie Gorge after thunderous rains. But it was the chance to see Ikara (Wilpena Pound) from the air that she found most astounding.

Looking at photos taken of this 17-kilometre-long mountainous arc from the road, it’s easy to suspect that it was carved out by a meteor strike - the land cast aside and upwards by the force of an imagined impact. Yet from above, you start to understand that this immense basin is instead all that remains of a mountain range, once higher than the Himalayas, that simply wore away over millennia. This is a place where eons are written into the earth.

When I go back to these images, I can picture myself in Ikara-Flinders Ranges. I feel the sun on my back, envision how the light must shift and dance, moving from the most vivid days to a pastel melange as the night draws close. I imagine watching on as the colour finally fades, and the constellations appear, the time-marked landscape entirely transformed by starlight. I want to be there, standing on the ochre earth, chasing wildflowers, being utterly dwarfed by all that remains of long-faded mountains and waterways. One day I’ll visit, but until then, I’ll keep finding the magic in photographs.

Words by Liz Schaffer